Sewing Rudi Gernreich's Kabuki Dress

Two years ago I attended my first Current Affair vintage show in New York. Current Affair happens twice a year in each city it's based in (New York, SF, LA) and some 200 vintage sellers come together in a convention space to sell in one place. Sellers really bring out some of their most exciting pieces and for me it was an amazing place to engage with the vintage community and see and touch clothing I would never be able to access otherwise - especially since some pieces are really museum worthy. Current Affair has since gone virtual and is currently stocked through Arcade Shops which is their co-op vendor site. As I was scrolling the Arcade Shops listings I found a Rudi Gernreich dress that really captured my attention. I absolutely love Gernreich's work, which is always brilliant and joyful and truly captures the spirit of the 60s, because Rudi Gernreich had such a hand in shaping the 60s through clothing and his influence is still all around us.

For a long time Gernreich was not taken seriously as a designer. In the 1960s and 70s his work was criticized for being unwearable, overly political, and meant to be photographed rather than worn. He was based in Los Angeles, not New York or Paris, and he mostly designed playful, avant-garde knitwear and intentionally political garments, some of which were sold in chain stores which further undermined his legitimacy in the eyes of the fashion press. When he won a Coty Award for his work in 1963, Norman Norell returned his Coty Hall of Fame Award because he hated Gernreich's work so much.

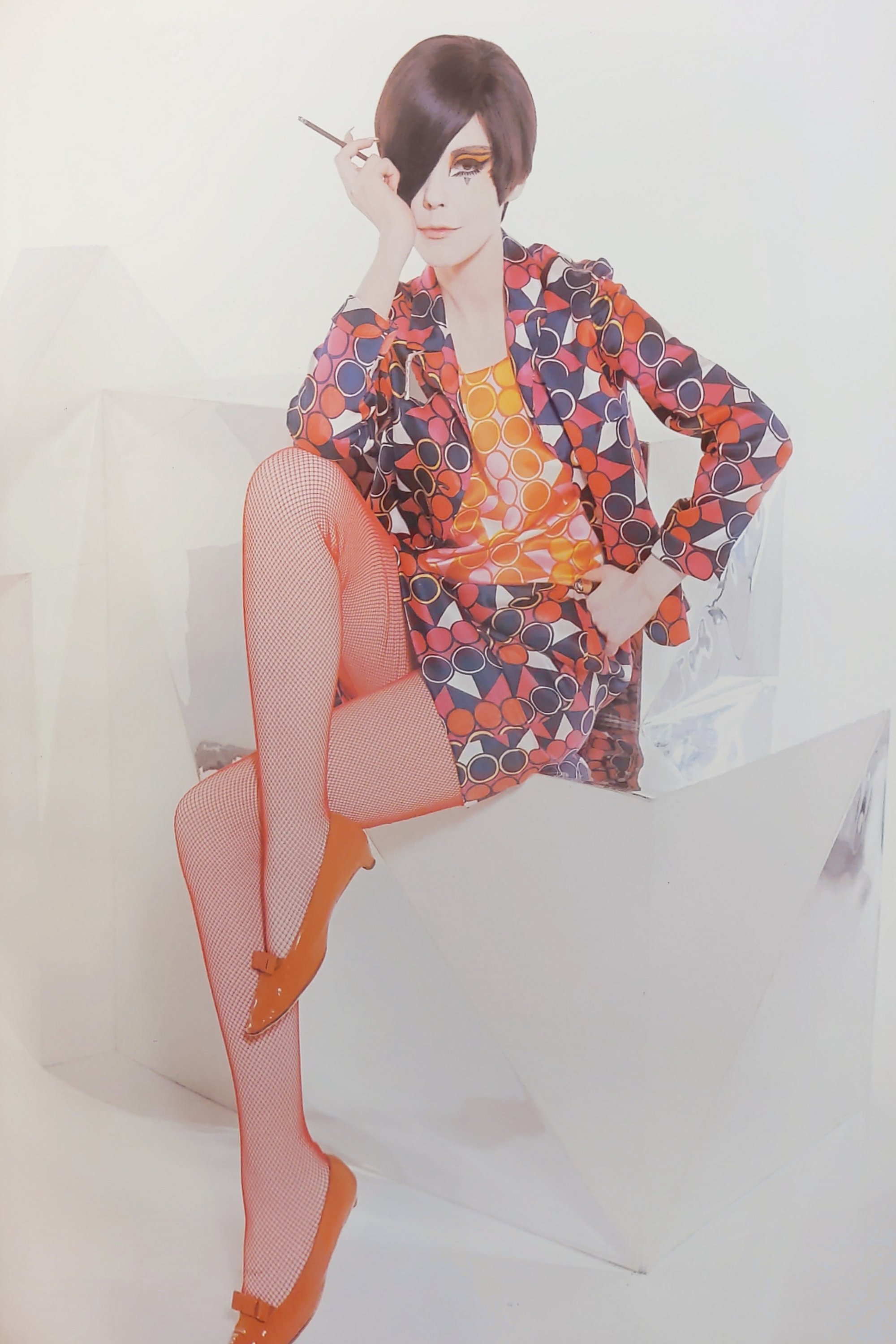

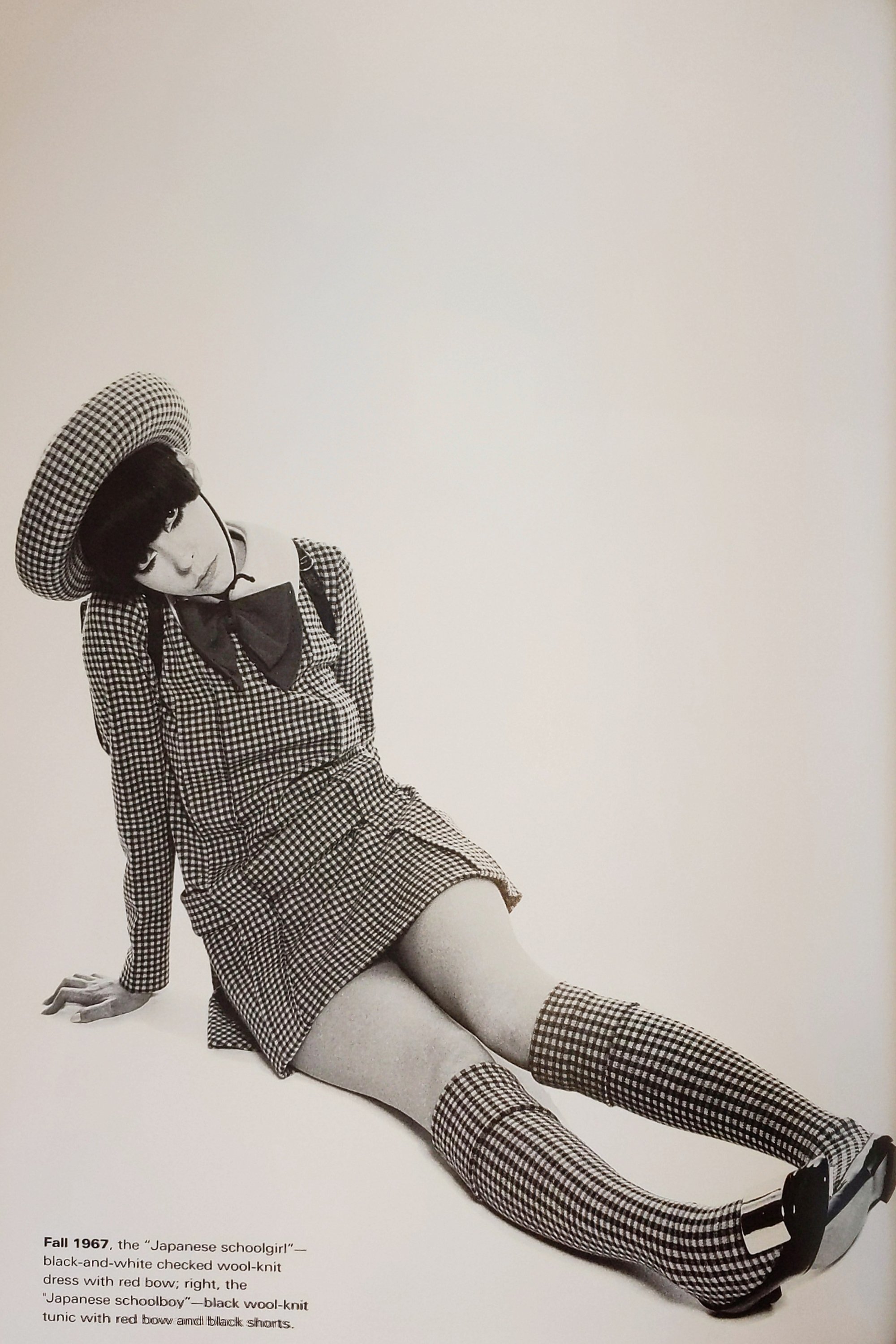

At this time the strict rules of couture were on their way out but Gernreich's clothing was considered alternatively too provocative or too accessible to really be serious fashion. His personal life was political and he allowed this to be reflected in his collections. Gernreich moved to Los Angeles with his mother in 1938, as a 16 year old, as they escaped Austria after its annexation. In 1950 he became a founding member of the Mattachine Society, an early gay liberation group, and in 1952 he was arrested for his sexuality in an entrapment case. By the 1960s he was designing under his own name and causing a fuss amongst the press and the fashion elite. His 1964 Monokini and 1967 "no" collection of sheer underwear revealed the wearer's body and he continued to push the boundary of nudity in clothing for his entire career. He often designed tight, fitted garments wearable by any gender and in 1970 shot a completely nude campaign titled "unisex." Gernreich's clothing reflected a love for youth culture, liberation, and protest. He was aware of the Japanese student movement and the Anpo protests throughout the 60s which mobilized Japanese citizens against American military occupation in Japan. He released the Kabuki dress in 1963 and the Japanese Schoolboy/Schoolgirl ensembles in the late 1960s in what reads as a show of support against American occupation. Gernreich took inspiration from everywhere and all his clothes were in direct response to the world he lived in.

What is openly political clothing today? I can think of plenty of transgressive fashion photography and advertising, most of it overtly sexual, like the 90s Tom Ford ads. Brands that do a lot of reworking and upcycling are political. Marc Jacobs feels political, at least personally, but a lot of politics in fashion now is very individualistic. Of course it's hard to distill global events into a piece of clothing but it could be interesting to try. Gernreich hit on a very unique combination of creating affordable ready-to-wear (he was very against inaccessibly expensive clothing) and making open political statements about both women's bodies and contemporary culture. Whether these designs felt a little too on the nose at the time I can't say; furthermore I think releasing a "Japanese schoolgirl" outfit today would be largely rejected. However as a product of the 1960s they stand as a remarkable testament to Gernreich's opinionated approach to the real purpose of clothing: as a tool for direct communication and utilitarian minimalism.

As usual I have gone off on a few different tangents, I never have a thesis to these things and I'm always trying to combine about 4 different ideas I have (the next one is all about reproductions or "copying" which is a topic I have come to find extremely boring and a black hole for nuance to vanish into) (the one after would be about woolen swimsuits) into one blog post which should really just be about... how I made the dress. So let's just talk about that.

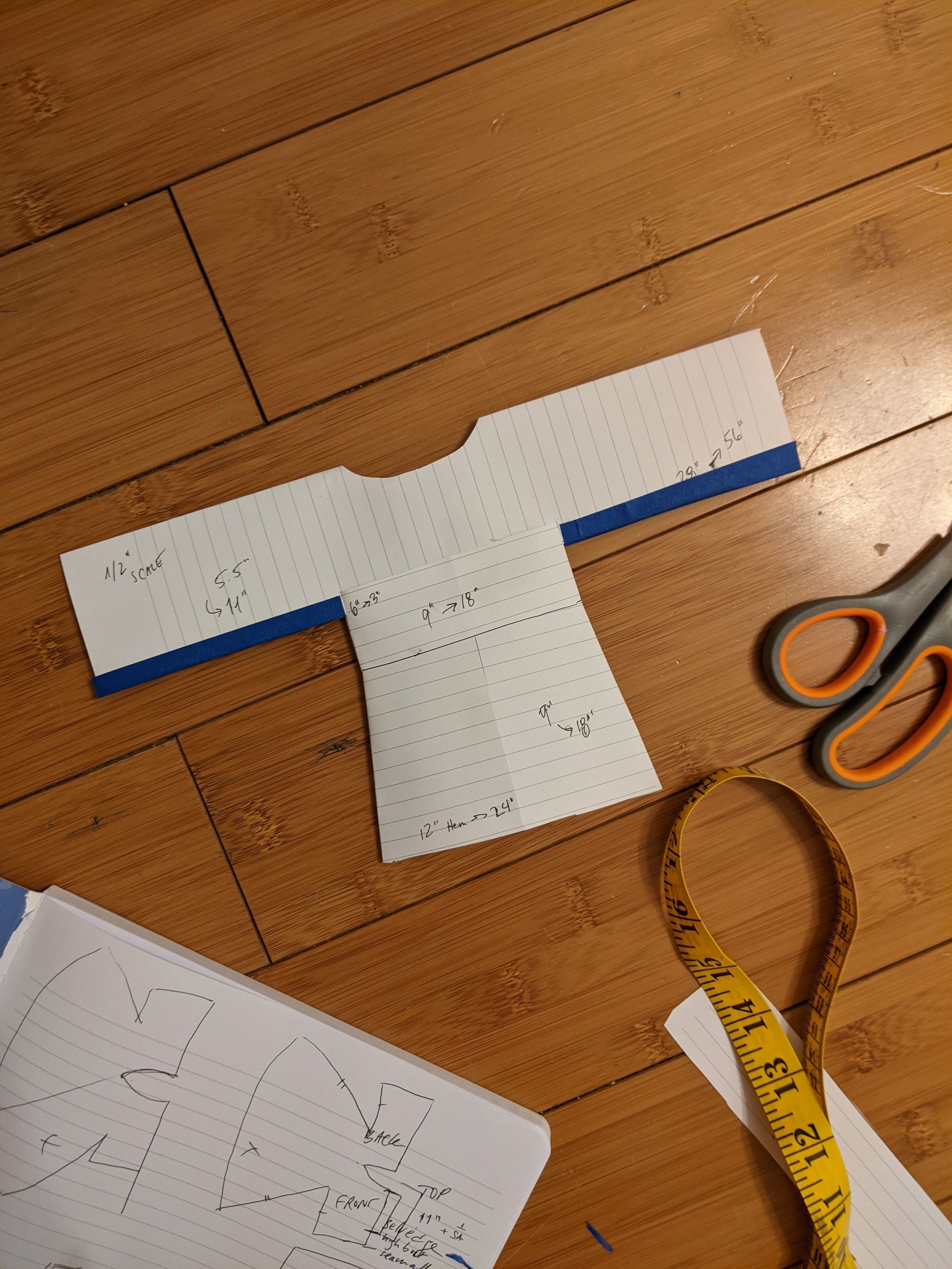

This dress looks really simple at first. However as I stared at it from every angle I realized a few important construction details.

- No seam at top of sleeve. This meant the bodice was cut out of a rectangle with a height of 2x the shoulder to bust measurement and sewn together at the underside of the sleeve much like my Issey Miyake coat! Of course there would have to be a cutout at the top for the neckline.

- Center seam on upper bodice. This meant the bodice was made of 2 rectangles, each with a width of 1/2 my total wingspan to include both the bust and sleeve in one piece.

- The only seam on the obi-style belt was in the back, so the belt is made of one rectangle.

- The only seam on the skirt was also in the back, but the bottom of the skirt is wider than the top. On close inspection there are four 1" pleats on the upper part of the skirt. I could not just cut 2 A-line skirt pieces for the front and back which is what I initially anticipated.

The first thing I did was to construct a paper miniature of the dress. This is a random technique I have used occasionally when I do patternmaking to plan out my work particularly when I am looking to copy existing work. It's not always good for patterns that use a lot of little pleats or darts (although a stapler can help with those) but I find it useful for planning and thinking through my work and the measurements of the different pattern pieces.

Then I made a muslin of the bodice. Because the sleeves intersected with the obi belt, I wanted to make sure I knew how to sew the upper bodice to the belt. I also needed to check that my bust measurements were correct. It looked pretty good. I also decided to keep the wider neckline that I had cut because I think it's prettier that way. Gernreich designed his Kabuki with a few different neckline cuts and closures.

I found the fabric on eBay. I wanted to find it all in wool like the original but it was really challenging to source diagonally-striped lightweight wool. Horizontally or vertically striped wool would mean that I would have to cut the entire dress on the bias which would have made it a lot stretchier (and I'm not confident I would be able to match the stripes? I'm unsure.) I ended up using a polyester double knit.

Then I began sewing the dress. All of the pieces were simple rectangles but the construction had its challenges. Fortunately there are many photos of the internals of the Kabuki dress which reveals that the obi is backed in a cotton fabric to prevent it from stretching down as the dress is worn (top left photo). I did a lot of hand basting to hold the facings in place and then tacked them down by hand. Ironically Gernreich would probably have rejected this as his approach to clothesmaking was so easygoing and often very imperfect: "Rudi didn't care if a perfect silk dress had an uneven hem," so says his muse Peggy Moffitt in her book about him. I faced the neckline with self fabric (bottom left). I faced the sleeves in the green fabric of the obi belt as I noticed it was done originally (right).

The purple tie belt is the only part of this piece that is not vintage and I ordered it from Katz Trimming, it's a knit foldover bias tape. I had never heard of knitted bias tape but I learned about it when I asked Lauren of Virtuous Courtesan on her Patreon and double checked with my sewing professor Dolores Lombardi at FIT. The metal zipper I put in is vintage. I searched pretty relentlessly for all these materials which were harder to find than I anticipated. I truly wish I had been able to source everything in wool but of course lucky Gernreich worked closely with Harmon Knitwear and I assume was able to design his own wool fabrics.

This dress came together pretty quickly and I am really pleased with how it looks. I've obviously been interested in working from designer patterns because I'm curious as to how designers I admire pattern their clothing. Those can be limiting because they are produced specifically for pattern companies but they also provide more complex insights into how some clothes are made. It would be more challenging to have made the Bill Blass jacket only from photos. Making a dress in this way was really interesting and a new experience for me. I was lucky that this dress is so well documented and has so little seaming but I feel like it was a good project for studying clothes for recreation. In the future I'm planning on copying an 1860s silk bodice that I own. (And about a million other projects.)

P.S.: A few days after I completed this dress I visited with my friend Suzanne who owns Via Vintage Vox Pop, a vintage archive she used to rent to designers and is now selling as she moves to another career after 30 or so years in the fashion industry. I noticed she had the Rudi Gernreich book that Peggy Moffitt wrote and commented on how much I love Gernreich's work. She mentioned that she had actually owned his "no" bra and sold it. Then she thought a little more and she pulled out a yellow dress attributed to Rudi's Harmon Knitwear line from the 60s! I almost fainted and of course I bought it immediately. I genuinely can't believe I own one of his pieces and I just feel lucky beyond belief to know Suzanne.